Cardiologists are taking a closer look at the possible long-term cardiovascular effects on COVID long-hauler patients who still show symptoms long after they should be recovered from the virus. Getty Images

With nearly a year of experience with the COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) virus, it has been found that some post-COVID patients experience long-term lingering coughs, cognitive issues and other complains months after they recover from the virus. These long-haulers are also appear to be having the heart issues as well. Determining the long-term impact of coronavirus will certainly be one of the top cardiology issues discussed in 2021.

COVID patient cadaver studies also raised questions on the long-term damage to the heart after it was found COVID kills cardiomyocytes.[1,2] But the question has been what is the long-term impact of this cardiac injury.

“So this is very much a story in evolution,” explained Aaron Baggish, M.D., director of the cardiovascular performance program, Massachusetts General Hospital. “I think early on in the COVID pandemic, it became quite clear that hospitalized patients, particularly those that were sick enough to make it to the ICU, a significant minority of them, anywhere from 20 to 30%, had evidence of heart injury. And that heart injury was really related to two different types of pathophysiology. The first was a response to the high levels of circulating stress hormones. And the second was direct viral invasion myocarditis. And that became an important therapeutic target for us early on in the course of this disease. But I think the question many of us are asking now is what would the long-term implications of this be, and perhaps more importantly, would we be seeing heart injury in folks that were infected with COVID, but not sick enough to come to the hospital.”

Qualifying COVID Cardiovascular Damage and the Role of Comorbidities in Mortality

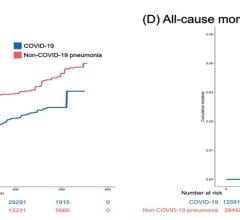

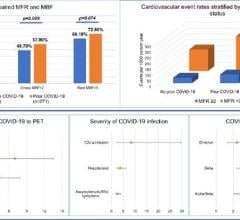

One study during the first wave of COVID found cardiac injury occurred in 19.7% of hospitalized COVID patients, and it was an independent risk factor for increased in-hospital mortality.[3] A more recent late-breaking study at the American Heart Association (AHA) meeting in November reported data from 14,000 U.S. COVID patients. It showed in-hospital mortality due to cardiovascular comorbidities ranged from 28.5 percent for patients with hypertension to 28.6 percent for those with diabetes, 25.5 percent for those with coronary artery disease, and 38.4 percent for those with heart failure.[4] But for the patients who do recover, it is not yet known if there is a lasting impact.

A German MRI study of 100 post-COVID patients revealed cardiac involvement in 78 patients (78%) and ongoing myocardial inflammation in 60 patients (60%).[5] This was independent of pre-existing conditions, severity and overall course of the acute illness, and time from the original diagnosis. These findings indicate the need for ongoing investigation of the long-term cardiovascular consequences of COVID-19.

“With the myocarditis, this is something that we've been seeing in some of the really, really, really sick COVID patients, but it's sounding like there might be signs of myocarditis even less sick patients,” said Todd Hurst, M.D., a cardiologist at Banner University Medicine Heart Institute, and an associate professor at the University of Arizona. “One of the things that we use to assess myocarditis is troponins, and we are seeing that pretty frequently. About 25% to a third of patients who are severely ill with COVID have evidence of troponin being elevated, indicating heart damage, but lots of different things can cause this. A more sensitive test would be an MRI of the heart, and there have been research reports of MRI abnormalities even in young athletes who had COVID. But we're not really sure what those abnormalities mean.”

While the acute inflammation and injury to the heart are seen in some COVID patients, the long-term effects of healed myocarditis is not completely unknown. Most infected patients experience mild, self-limiting symptoms, but are not undergoing regular ECG or cardiac imaging to monitor them.[6] Some of these patients may be at risk for subsequent arrhythmias.

Evidence for pericarditis and myocarditis was also found in a Spanish study of 139 healthcare workers who had COVID.[7] About 10 weeks after infection, the patients underwent ECG, lab tests and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging. The prevalence of pericarditis or myocarditis was found in up to 40% of cases. Pericarditis coexisted with some degree of concurrent myocardial inflammation in 11% of cases.

Chest pain, dyspnoea or palpitations were observed in 58 (42%) participants. ECG abnormalities were found in 69 (50%) of patients. CMR abnormalities were found in 104 (75%). Isolated pericarditis was diagnosed in 4 (3%) participants, myopericarditis in 15 (11%) and isolated myocarditis in 36 (26%). NT-pro-BNP, a non-active prohormone that is released in response to changes in pressure inside the heart usually related to heart failure or other cardiac issues, was elevated in 11 (8%) of patients. Troponin was elevated in 1 patient.[7]

CDC Recognizes COVID Long-Haulers

Thousands of patients have reported symptoms ranging from shortness of breath, chronic fatigue, brain fog that causes difficulty concentrating, anxiety and stress. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) started reporting these issues last July.[8] In the study the CDC posted, more than a third of people had not returned to their usual state of health two to three weeks after testing positive.

Last summer, physicians began suspect there may be long-term damage not just in lungs, but in the heart, immune system, brain and and other organs. Evidence from previous coronavirus outbreaks, especially the 2002 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic, suggested these effects may last years.[9]

Hospitals Are Creating COVID Clinics to Monitor Long Term Effects

To get a better handle on long-hauler patients, numerous hospitals started creating Post-COVID monitoring clinics, including the University of Chicago, University of Colorado Health, St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, Mt. Sinai in New York City, and Cedars Sinai in Los Angeles. In November, Cedars created what is believed to be the first dedicated cardiac post-COVID clinic for long-haulers.

“When folks come to us after initial resolution of COVID, infection, either asymptomatically or with persistent symptoms, particularly among those that have disabling persistent symptoms, the basic assessment would be an echocardiogram, a 12, lead ECG, blood testing for cardiac troponin to rule out active myocarditis,” Baggish explained. “And then some form of ambulatory monitoring to screen for the heart rhythm disturbances that we know would increase risk of something bad happening like sudden death.”

Athlete COVID Long-hauler Cardiac Research

In January 2021, the AHA and the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM) joining forces to accelerate a critical new research initiative studying cardiac conditions in athletes who had COVID-19. Both organizations hope to speed up research to find new insights on the impact to the cardiovascular system of college athletes and to understand when it is safety for them to return to play.

Sports medicine and cardiology experts at Harvard and the University of Washington created a national registry research database to track COVID-19 cases and heart-related impacts in NCAA athletes to drive improvements in screening and to better understand cardiac involvement in college athletes with prior infections. The NCAA and has more than 60 schools currently contributing to the new registry.

The Outcomes Registry for Cardiac Conditions in Athletes (ORCCA) has already collected data from more than 3,000 athletes. The AHA will use its Precision Medicine Platform (PMP), a secure cloud-computing platform hosted by the Association’s Institute for Precision Cardiovascular Medicine to facilitate the research.

“There have been many high-profile cases of athletes at the collegiate and professional levels showing myocarditis after COVID-19,” said Mariell Jessup, M.D., FAHA, cardiologist and chief science and medical officer for the American Heart Association. “Research and data are key to answering the ongoing debate in college sports about the safety of return to play and guidelines on the appropriate assessment of the athletes.”

Baggish is involved with the registry. He is an expert is sports medicine and involved in the Boston Marathon and the professional sports teams in Boston. He also helped author an JAMA article on recommendations for when it is safe for athletes infected with COVID to return to play.[10]

“When we first started learning about the relationship between COVID and heart injury, we were obviously very concerned that when student athletes would get back onto the playing field, particularly those that had significant COVID infection that they would harbor heart injury or in worst case, active myocarditis that would put them at risk for sudden death,” Baggish said. “What we started to see dealing with many athletes, literally hundreds of athletes at the professional and collegiate level, is that we weren't seeing anything in the way of cardiac injury in people that had mild or asymptomatic disease. So we made a call to really focus the screening to those that had either moderate or severe COVID infection.”

Other COVID Surveillance Registries

There were also several COVID registries and studies created to track the cardiac impacts of COVID. Here are a few they will likely yield new information later in 2021.

The AHA created its COVID-19 Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Registry in April 2020 to capture data on patient clinical characteristics, medications, treatments, labs, vitals, biomarkers and outcomes for adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19. This includes those without a history of cardiovascular disease or stroke. To date, more than 22,000 de-identified patients’ health measures and data points are available in the registry.

The Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) also launched the North American COVID-19 Myocardial Infarction (NACMI) Registry enrolls any COVID-19 positive patients with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) or new-onset left bundle branch block with a clinical correlate of myocardial ischemia. The data will be compared to an age and gender-matched control population from the existing Midwest STEMI Consortium.

The American College of Cardiology collects COVID-19 data through the NCDR Chest Pain – MI Registry and the CathPCI Registry. The goal is to better understand the relationship between COVID-19 and heart disease and maximize data on the cardiac impact of the virus.

In the U.K., the British Heart Foundation has started seven COVID studies to better understand the effect of the virus on the heart and what it means for long-term impacts. Cardiac MRI and computed tomography (CT) will be used in two of the studies.

One of these projects will follow patients 6 months after their recovery to understand the extent and persistence of damage to the heart and other organs. Co-led by Professor John Greenwood, NIHR Leeds CRF cardiovascular director, and Professor Stefan Neubauer, NIHR Oxford BRC Imaging Theme lead and Steering Committee member of the Oxford BHF Centre of Research Excellence, the project forms part of a larger national study, the Post-Hospitalisation COVID-19 study (PHOSP-COVID). That study, launched in July 2020, will follow up to 10,000 patients who have been hospitalized with COVID-19.

More than 300 patients recovering from severe acute symptoms of COVID will be have measurements of biomarkers and cardiac magnetic resonance images (MRI). In six of the centers, over 600 patients will undergo additional tests, including whole-body MRI, chest computed tomography (CT) scans and cardiopulmonary exercise testing. The CT scans will be analyzed for evidence of inflammation. Quality of life and mental health questionnaires will also be completed. This will help the team define the damaging effects of the virus on the brain, lungs, heart, liver, kidney, exercise capacity, and overall well-being.

Another study will use artificial intelligence (AI) analyze CT scans measure to measure the level of inflammation in the heart. These AI methods were developed by Professor Charalambos Antoniades, BHF Senior Clinical Research Fellow and Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine at the University of Oxford, who will lead the project with collaborators across the U.K. This study will use previous CT scans of patients with existing heart disease and repeat CT scans after infection has subsided. This will allow a direct comparison of inflammation before, during and after infection to understand whether COVID has lasting effects on heart health.

"This virus may be a respiratory infection, however, the most common underlying health conditions in those who die are cardiovascular,” explained Professor Sir Nilesh Samani, medical director at the British Heart Foundation. “People with heart disease are among the most likely to die from the virus and the risk for people with diabetes is two to three times higher than the general population. And we are rapidly learning that the virus can have devastating effects on the heart and circulation and increase the risk of blood clotting, heart attacks and strokes.”

Doctors Need to Avoid Ignoring COVID Long-Haulers

There is a tendency by some physicians to write off many patient complains as being in their head, rather than being caused traceable medical reasons. This has occurred in patients who take statins, had stents impacted and continue to to have chest pain, and in some medical conditions such as chronic fatigue and Lyme disease. Since this is a new disease, many experts are warning that physicians need to pay attention and data needs to be collected to determine if there is an explanation for complains by COVID long-haulers.

“I really do worry about confusion within the medical community as to whether this exists or not, and how that there are going to be folks that take this very seriously and are effective for their patients, and folks that don't blow their patients off. And that will invariably do more harm than good,” Baggish said.

He draws similarities between COVID long-haulers and the early days of understanding Lyme disease.

“There were a small but important subset of people with Lyme that went on to develop chronic symptoms. And to this day, doctors still don’t agree about whether there's such a thing as chronic Lyme,” Baggish said. “And I suspect we will have a similar dialogue around COVID-19, in which there will be providers that identify this as a legitimate diagnosis and some that think about this more as a as a supratentorial diagnosis, meaning a diagnosis that patients may bring, but don’t really have any firm pathophysiologic background. So I just think we need to keep a very open mind about what it means when a patient comes into the office and complains of long lasting symptoms, and we can't find an explanation for it.”

One issue that may complicate things is that cardiomyopathies of unknown origin were something seen on a regular basis prior to COVID, Hurst said.

“The cellular damage that this virus causes is incredible. We haven't seen anything like this before, Hurst explained. “I’ve seen a case or two of people that seem to have ongoing heart muscle weakness or cardiomyopathy after COVID infection. Now, is it really cause and effect, or is even associated? That’s impossible to answer at this time, we just need more time and more data. But the number of people and the number of cases that are being reported, it's certainly concern.”

Related COVID Long-hauler Content:

What We Know About Cardiac Long-COVID Two Years Into the Pandemic (Jan. 2022 update)

VIDEO: Long-term Cardiac Impacts of COVID-19 Two Years Into The Pandemic — Interview with Aaron Baggish, M.D. (Jan. 2022 update)

VIDEO: What Are The Long-term Cardiac Impacts of COVID-19 Infection (Jan. 2022) — Interview with Todd Hurst, M.D.

VIDEO: What Are The Long-term Cardiac Impacts of COVID-19 Infection — Interview with Todd Hurst, M.D.

COVID-19 Changes Properties Blood Cells

VIDEO: Lingering Myocardial Involvement After COVID-19 Infection — Interview with Aaron Baggish, M.D.

Tsunami of Chronic Health Conditions Expected Due to COVID-19 Disruption of Healthcare

Cedars-Sinai Launches Clinic to Manage Long-Term Heart Health Issues in COVID-19 Patients

VIDEO: Antithrombotic Prophylaxis in COVID-19 Patients — Interview with Behnood Bikdeli M.D.

COVID-19 Registry Tracks Cardiac Health of College Athletes

Cardiac MRI Shows Lower Degrees of Myocarditis in Athletes Recovered from COVID-19

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the Heart—Is Heart Failure the Next Chapter?

PHOTO GALLERY: How COVID-19 Appears on Medical Imaging

Heart Damage Found in More Than Half of COVID-19 Patients Discharged From Hospitals

Overview of Randomized Trials of Antithrombotic Therapy for COVID-19 Patients

COVID-19 Can Kill Heart Cells and Interfere With Contraction

7. Rocio Eiros, Manuel Barreiro-Perez, Ana Martin-Garcia, Julia Almeida, et al. Pericarditis and myocarditis long after SARS-CoV-2 infection: a cross-sectional descriptive study in health-care workers. Cardiac COVID-19 Health Care Workers study (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04413071) doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.12.20151316

March 20, 2024

March 20, 2024